How German Is It: An endless, shifting hall of mirrors where every image is haunted

How German Is It: An endless, shifting hall of mirrors where every image is hauntedby Leslie Camhi, Village Voice, November 28th, 2005

I would love to know what the photographer Collier Schorr said to Jens F., a German adolescent whom she met on a train, in order to convince him to pose for her. Schorr, who is American and Jewish, spends her summers in an intensely Catholic region of southern Germany. In a brief, eloquent essay published in her richly layered and complex new artist's book Jens F. (Steidl/MACK), she recounts that, during that particular journey through Hitler's former heartland, she was "reading Primo Levi's Survival in Auschwitz, which was my self-imposed punishment and seemed a fair compromise after reading Cynthia Ozick's essay, 'Why I Will Never Go to Germany.' "

Schorr was 37 at the time of this encounter, in 2000, while the red-haired Jens still possessed the soft, inchoate beauty of boyhood. I assume they spoke German. It's likely the question "What are you reading?" would have been a conversation-stopper. Did they chat about sports or movies, or the slow-moving train? Was he curious about New York and the life she led there?

Did she say, There's an American artist named Andrew Wyeth, long out of favor in the avant-garde art world precincts where my work is welcomed. He drew and painted a woman, his German-born neighbor Helga Testorf, in secret for some 15 years. I'd like to do something similar with you—to pose you as he did her, to fashion you in another's image while mining your private moods and least gestures, to record the changing lines of your body and the gradual hardening of your flesh, occasionally diverting my attention to others; in short, to attempt to possess you, as any portraitist does his or her model, knowing all the while that you will elude me, that the search is all.

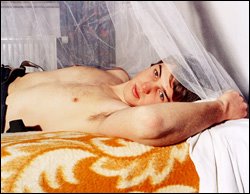

However put—and who, in truth, is privy to the furtive, often unspoken negotiations between artist and subject?—the deal was struck. "Collier Schorr: Jens F.," the show currently at Andrew Roth gallery, includes single and collaged photographs produced over five years, mostly of Jens, clothed at times in German military surplus or semi-nude and striking poses inspired by Wyeth's Helga. Included are a few pictures of Jens's sister, a blond-braided mädchen in a field (an ideal of purity dear to Nazi propagandists) with an uncanny resemblance to Helga's daughter, who also modeled for Wyeth. Cameo appearances by a small cast of stand-ins and body doubles—a girl who looks like a boy, a friend of Jens with whom we occasionally confuse him, and an American woman who is Helga's doppelg matters even further.

The result is an endless, shifting hall of mirrors, where every image is haunted by the ghost of at least one other, where the distances between painting and photography, boyhood and womanliness, conceptual art and classicism, figure and ground, guilt and innocence, Wyeth's high-WASP attraction to Helga's Teutonic heritage and Schorr's Jewish ambivalence regarding the ghosts haunting German soil—to mention only a few—are temporarily collapsed, and near-opposites are rendered interchangeable. Schorr's handwritten notes, scribbled in margins of her collages and on the pages of Jens F. (which meticulously reproduces a dense scrapbook of Polaroids and contact prints that Schorr pasted into a catalog of The Helga Pictures), mention Henry James, whose American characters went to Europe only to find their own shattered reflections. One is reminded of Proust (and of Hitchcock in Vertigo), for whom love—the desire to possess another—is never an original feeling but an illusory edifice resting on the unstable foundation of past affections.

That this exchange took place in 21st-century Germany raises its stakes inordinately. Schorr, best known for her tender, silken, vulnerable depictions of testosterone-driven youths—most recently, New Jersey private-school wrestlers—has passed this way before, with a series portraying German adolescents in woods and fields, both nude and wearing military garb, including what appear to be fragments of Wehrmacht uniforms. The pictures were at once unsettling—in an interesting way—and irksome in their coyness. The display of Third Reich insignia remains illegal in Germany, presumably because it still inspires in some people a rather unhealthy nostalgia. Schorr works intuitively, and ambiguity is a key component of her art, but was it worth breaching this particular taboo for what seemed a private fantasy? It's hard to be sure. But the broader work reveals those photographs as one episode of a sustained investigation into landscape and memory, an attempt to unravel, ever so slightly, the tightly knit relation between "blood and soil" (as they once called it in Germany), nationhood and identity.

No comments:

Post a Comment