Biennial in BabylonCrossing swords with conventions that have brought us to the brink of madness

by Jerry Saltz Village Voice March 1st, 2006 5:40 PM"Day for Night" is the liveliest, brainiest, most self-conscious Whitney Biennial I have ever seen. In some ways it isn't a biennial at all. Curators Chrissie Iles and Philippe Vergne have rebranded the biennial, presenting a thesis, not a snapshot, a proposition about art in a time when modernism is history and postmodernist rhetoric feels played out. This show, and the art world, are trying to do what America can't or won't do: Use its power wisely, innovatively, and with attitude; be engaged and, above all, not define being a citizen of the world narrowly.

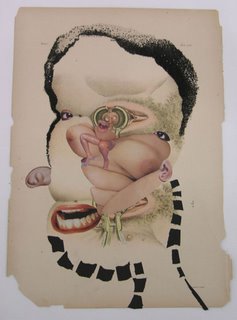

"Day for Night" is filled with work I'm not interested in; it tries to do too much in too little space; it is often dry. Nevertheless, the show is a compelling attempt to examine conceptual practices and political agency, consider art that is not about beauty, reconsider reductivism, explore the possibility of an underground in plain sight, probe pre-modern and archaic approaches, posit destruction and chaos as creative forces, and revisit ideas about obfuscation and anonymity. This show is less market driven than usual—in fact, it attempts to cross swords with conventions that have brought us to the brink of madness. It's also an anti-manifesto, taking on romanticism, expressionism, and decorative psychedelia.

Kant said, "The day is beautiful; the night is sublime." "Day for Night" isn't about the sublime in any old-fashioned awe-inspiring sense, but it hints at types of darkness. All the windows of the museum have been boarded up. "Day for Night" will be seen by the masses, but it isn't really for them. It is the art world meeting around fires, taking stock, and trying to work things out.

This biennial is positively un-American. Iles and Vergne are European, more than a quarter of the 101 participating artists were born outside the U.S., and sundry others live elsewhere part-time. Even the show's title comes from a French movie, François Truffaut's 1973 film, although the movie's original title describes the biennial and the country better, The American Night.

The show is not without problems. Sometimes the curators seem to be second-guessing themselves before they've even first-guessed. Their propensity for cool art by cool artists suggests "Day for Night" could be called "The Black-and-Silver Biennial." The outstanding catalog includes flashy foldout artist pages and excellent essays by the curators, critic Johanna Burton, and gallerist Lia Gangitano, as well as an ingenious "quiz" by critic Bruce Hainley. But the exhibition also suffers from such aggravating tics as an invented curator and a low percentage of women (25 percent) when you count only the individual artists on view in the museum. Good paintings are present, notably by Mark Grotjahn, Mark Bradford, Rudolf Stingel, and Marilyn Minter. Yet these curators, like so many curators these days, don't really get painting's alchemical qualities or appreciate how old mediums can carry new thoughts.

This brings us to an irksome feature of this show and many like it: The curators regularly treat two-dimensional media as if they were second-class citizens, jamming them in, splitting them up, or using them as filler. Meanwhile, conceptual work, video, and installation are given ample space. Jennie Smith, Kelley Walker, and Adam McEwen belong in the biennial, but all are short-changed. Some things just don't work: Jutta Koether belongs but her installation feels forced; paintings by JP Munro, Spencer Sweeney, Todd Norsten, Chris Vasell, and Monica Majoli are unimpressive to say the least. Nari Ward is good but this wasn't a biennial year for him; Peter Doig's paintings aren't up to stuff; videos by Jim O'Rourke, Jordan Wolfson, and Mathias Poledna are all weak; Paul Chan's floor piece is evocative but unoriginal.

A number of artists stand out. Especially impressive are Sturtevant's room of art that looks like Duchamp's work but throws representation out the window; Dorothy Iannone's video of herself climaxing (as she says, "The one fleeting moment when you can see the soul as it passes over the face"); Billy Sullivan's heartrending Nan Goldin–like slide show depicting an afternoon in a life and a whole life simultaneously; Robert Gober's journey into hatred; Angela Strassheim's penetrating photographs of people who are living more for the next life than this one; Jonathan Horowitz's 19 portraits of the 9-11 hijackers placed surreptitiously throughout the museum; photos by Florian Maier-Aichen, Zoe Strauss, and Anne Collier; Trisha Donnelly's blasting sound piece. Also, don't miss the terrific videos by Francesco Vezzoli, Cameron Jamie, Pierre Huyghe, the collective Don't Trust Anyone Over Thirty, and especially Ryan Trecartin's retina-bursting all-pores-open A Family Finds Entertainment.

Weirdest of all is a 1991 painting by Miles Davis. Since there is no Davis entry or artist page in the catalog, my own paranoid fantasies and assorted rumors have led me to believe that the painting was submitted by that true artist of the American night, David Hammons. Finally, to anyone who thinks that the Peace Tower, right now on Madison Avenue in front of the Whitney but originally built in 1965 to protest the Vietnam War, is silly or ineffectual: Now is the first time it has needed to be built again.

Flaws and all, "Day for Night" speaks to a nation that is no longer an ideal but only a country. That makes this the Post-America Biennial.

Telepresence & Bio Art: Networking Humans, Rabbits, and Robots by the artist Eduardo Kac.

Telepresence & Bio Art: Networking Humans, Rabbits, and Robots by the artist Eduardo Kac.